Connecting people to art

A conversation with BMAC’s Sarah Freeman, Exhibitions Manager & Coordinator of Education Programs

Sarah Freeman joined the staff of the Brattleboro Museum & Art Center in 2015. Before joining BMAC, Freeman was Public Education Manager at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum in New York. Her previous positions include Deputy Head of Education at Dulwich Picture Gallery in London and roles at The Lighthouse Centre for Architecture and Design in Glasgow, Scotland, and the Center for Arts Education in New York.

BMAC: What do you do in your role as BMAC’s Exhibitions Manager & Coordinator of Education Programs?

Freeman: My job has three main parts. As Exhibitions Manager, I work with curators and artists to develop and present all of the 20 to 25 exhibits at the Museum every year, from the initial identifying of artists all the way to getting their work physically here, hanging it on the wall, and making sure that it’s safe and sound and looking the way that it should. My job also now sometimes includes curating, which is really exciting.

Freeman and artist David Rios Ferreira at the opening of And I Hear Your Words That I Made Up at BMAC, June 2018, Freeman’s curatorial debut.

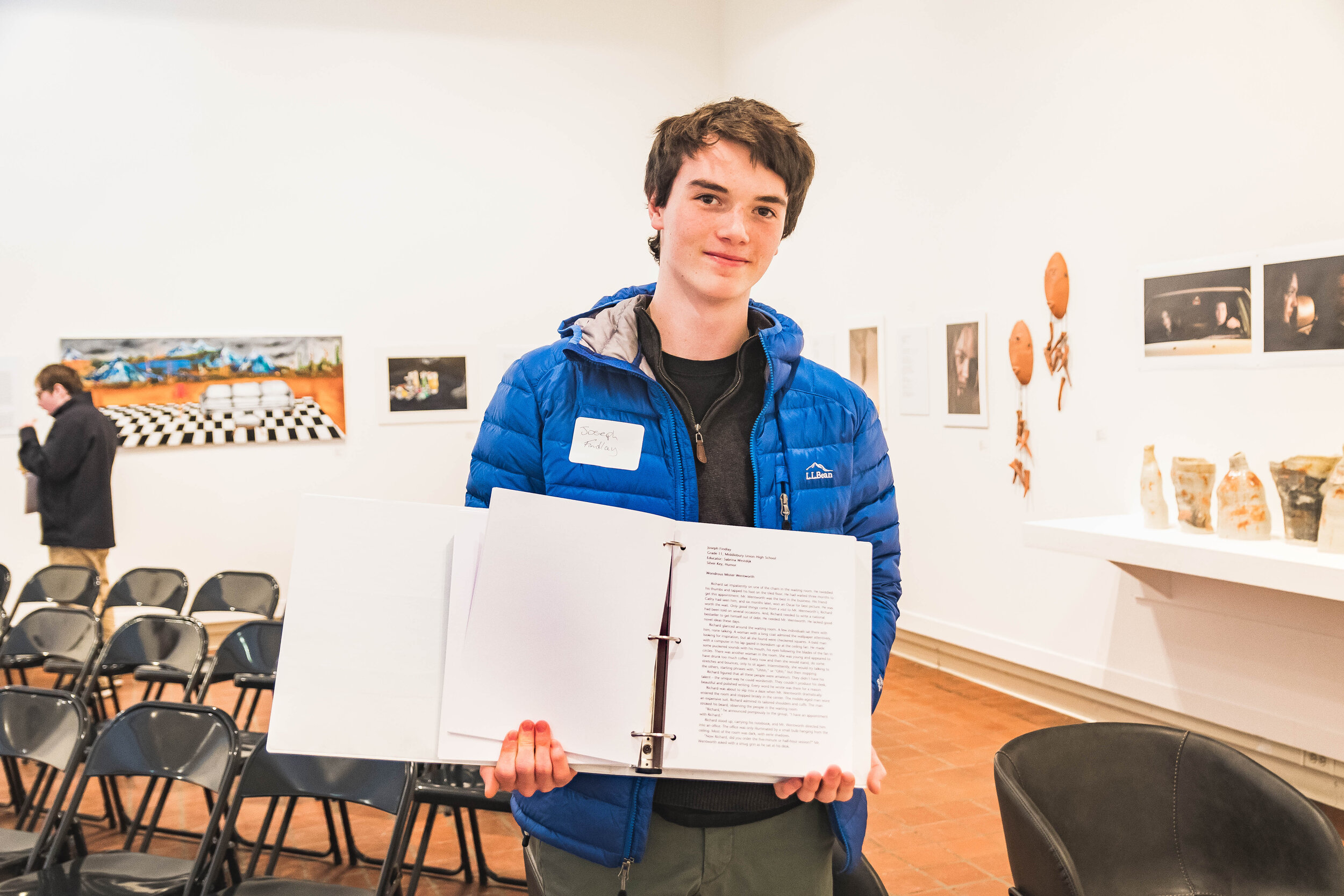

As the Coordinator of Education Programs, I oversee the Vermont Scholastic Art & Writing Awards. BMAC is the regional affiliate for the national program, which celebrates achievements in art and writing by students in grades 7 through 12. Each year, BMAC receives 500 to 600 individual submissions from students around Vermont in 25 or so categories—jewelry, printmaking, drawing, ceramics, fiction, journalism, personal essay/memoir, humor, science fiction, and so on. We work with professional artists and writers to judge submissions. The work that receives awards is exhibited here at the Museum in late winter and early spring.

Scholastic really encourages and celebrates creativity and personal expression. Being part of it is an amazing opportunity to see what’s going on in terms of creativity among young people in the state. There are so many different artistic techniques on show, and there is a really exciting range of personal voices and visions. The Awards really try to elevate and celebrate that. Originality, technical skill, and personal voice or vision are the criteria, so part of the program is about helping students find out who they are through their creative work. Scholastic was started to address an imbalance in a lot of schools, where schools were celebrating athletics and not focusing as much on creative pursuits.

I also manage BMAC’s Head Start with Art program, which sends two teaching artists into 15 Head Start classrooms in Brattleboro and Westminster, Vermont, numerous times each year to provide hands-on art, music, and movement sessions for infants and preschoolers. Those are really wonderful sessions. They do a lot of exploration of materials, thinking about pattern and color, and not only making art but building a vocabulary and an understanding of the materials used to make art. The program gives infants and toddlers a safe, warm environment to learn in.

The third part of my job involves writing grants for BMAC, which allows us to do more of what we want to do.

BMAC: You've worked at museums in New York City, Glasgow, Scotland, and London. What did you learn from those experiences that is relevant to your work now?

Freeman: My first job out of college was working at an art gallery in New York that focused on German and Austrian Expressionism and American folk art. I got to be really up close and personal with the art—Egon Schiele, Gustav Klimt. It was an amazing experience, and I learned so much, but I also learned that I wasn’t particularly interested in selling art. I decided to focus more on helping other people find out what role art could play in their lives.

I worked next at a New York grantmaking organization, working with schools and teaching artists. For some students, art is their therapy, their way out, and their happy place. It was really exciting to be a part of an organization that was helping teachers figure out how to encourage that in their students. Art is something that you can’t do wrong, and teachers could sometimes have a tough time with that. The wonderful thing about art is that people are approaching it from their own lived experience and their own point of view—so it might not be good, but it’s not right or wrong.

Then I met my husband, who is from the UK, and I moved to Glasgow to be with him. I worked at The Lighthouse Centre for Architecture and Design. From there, we moved down to London, and I got a job at Dulwich Picture Gallery, England’s oldest purpose-built art gallery-slash-museum. It opened in 1811. They have an amazing collection of Baroque Old Master paintings. They had an education department that was doing really cool, innovative, and kind of off-the-wall stuff based on these dark brown paintings of bald men with beards. Dulwich is this quiet, hallowed place where people are looking at Rembrandts and Rubenses and not talking, and the floor is creaking and the lighting is very dim, and then you’d go around the corner, and there would be this group of school kids performing this crazy song that they've written about one of the paintings, accompanied by one of the teaching artists on keyboard. We did a lot of work to try to open up the museum to non-traditional audiences, making these centuries-old paintings relevant, helping people feel more connection to the artwork. That experience made a big impression on me, and it’s influenced my work here at BMAC.

BMAC: What brought you to Brattleboro, and what has led you to stay?

Freeman modeling a hand-screened kimono at Cooper Hewitt Design Center in Harlem, during a "katagami" and "katazome" demonstration by master Japanese artisans.

Freeman: After we were in London, we moved back to New York, and I worked at Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. But I grew up in Vermont, and my family was here. After a few years, New York felt pretty exhausting, and we realized we could go somewhere else. We moved to Vermont at the end of 2014, and I started at BMAC six months later.

BMAC is by far the smallest museum that I’ve ever worked at. I like small museums a lot. I think that they have a lot more flexibility and can be really nimble. You can try stuff out more easily, and you can pick yourself up and dust yourself off and change course more easily than at a big museum. It’s a lot more fun. You don’t feel so bogged down. Being a museum of this size in a town of this size makes sense. It’s fairly small town, and we’re a fairly small museum, but we do a lot of cool stuff. And I think that will continue, and we’ll do more and more. The people who work here are so great and interesting and intelligent. I really enjoy bouncing ideas off each other and thinking about new ways to get people involved with the Museum.

BMAC: You curated Fafnir Adamites: Interfere (with), an installation that opened at BMAC on October 4, 2019. What was the curatorial process like for you?

Freeman: This is the second exhibit I’ve curated for BMAC. Before that, I had never done curating before. It’s a nice example of the flexibility and opportunity that small museums provide. I was able to say, “This is something I’m interested in. I have this idea—what do you think?” That’s definitely not something that would’ve happened at a larger museum. Being a contemporary non-collecting museum is very unique thing and has its own challenges, but there’s so much opportunity baked into that structure.

Fafnir does a lot of large-scale installation work that uses fiber, fabric, textiles, traditional craft processes to make forms or structures that have an improvisational or chaotic quality. The nature of the process changes the materials in a way that can’t be controlled or foreseen. In the current piece on show, Fafnir has done felting with burlap, and the wetness of the felt expands and constricts the burlap in unpredictable ways.

There had to be a lot of trust on both sides. Fafnir had to trust us to interpret their vision of what the work would look like, and we had to trust that the piece, which we had never seen before, would work in the space.

Fafnir Adamites, Interfere (with), felted wool and burlap, [installation view].

Photo credit: Sam Smalley

The work itself looks very weighty and dense. What a lot of Fafnir's work is reflecting is the weight of traits and inherited trauma that can be imprinted on people’s DNA and passed down from generation to generation. Using these repetitive physical processes allows time and space to deal with inherited trauma. The piece itself looks map-like and has underlying structures that reflect how people make sense of and cope with their own inherited trauma. It is heavy, but it’s a tool for coping, and it’s a complicated object that serves as acknowledgement and testimony. It also acts as a kind of self-care object.

It’s an interesting relationship, and installing it and seeing how it reflected the idea of inherited trauma and epigenetics was really exciting. The idea is remarkable.

BMAC: What do you see as BMAC's role in southern Vermont and in the museum world?

Freeman: One of the things that BMAC does is to work to make art accessible. With contemporary art, that can be really challenging. Sometimes people find contemporary art unapproachable and don’t “get it” or feel like it’s not for them. At first, the viewer may not always see the technical skill, or the hand of the artist, or the intention and work that went into the piece in the same way as with more traditional artwork. People can often feel turned off by it and therefore turned off by art in general, which to me is really sad, and a missed opportunity.

There are folks who go to museums and feel like they don’t belong there, or that people are judging them for not getting things or not liking things. Art is so subjective that it provides a great opportunity to have a conversation about why you like or don’t like something, how it makes you feel. At some museums the people who work there don’t even have the opportunity to go into the galleries. You’re in your office all day, and you don't have a connection with the people who are coming to your museum. At a small museum like this one, you get to have those conversations about art. And with contemporary art, there’s an actual living artist who can talk to you and answer your questions. Many of our artists attend our exhibit openings and give talks at the Museum. So the viewer realizes that there is a person who made this, and they’re right here, and you can talk to them.

Photo credit: Jeff Woodward

BMAC is such a friendly, welcoming place. We share work that we really love; we're excited about it, and we want to share it and talk about it. Because we don’t have a collection, we get to show what we want to show. It can be challenging, because you don’t know what will be next, and it might be very difficult to install or to light. You have to be really nimble.

What I really want to do in my work is to help people connect with art by whatever means they want to come to it, and see how it could be part of their lives.

![Fafnir Adamites, Interfere (with), felted wool and burlap, [installation view]. Photo credit: Sam Smalley](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5cdc4866ebfc7f30af34f660/1573830415039-3ZVSW9OTDP3GQ4YTT3QH/BMAC2019-103.jpg)