“Speaking these stories gives people like us power”

In connection with Jennifer Mack Watkins: Children of the Sun, BMAC presented “Black Representation in Children’s Literature,” a conversation with three acclaimed African American children’s book authors and illustrators: Rio Cortez, Daniel Minter, and Javaka Steptoe.

The following conversation is excerpted from the live Zoom event and edited for clarity. A recording of the full event is available here.

BMAC Director Danny Lichtenfeld: As a child, were there books that made a lasting impression on you? Do any of them continue to influence you today?

Daniel Minter: I grew up in a place where there were not a lot of children’s books that had images that I could see myself in. The ones that I do remember are not flattering and are more likely damaging. The books that I do remember having a great influence on me were not really children’s books. There was a collection of short stories from Harlem Renaissance writers that I came across at a really young age. A story by Zora Neale Hurston stood out to me because of the dialect: I felt like it was the first time that I had seen language written in the way that the people around me talked. That left a huge impression on me, and it’s still with me today.

Javaka Steptoe: Ferdinand the Bull, Why Mosquitoes Buzz in People’s Ears, The Chronicles of Narnia, and the story about Brer Rabbit and the tar baby. What makes Ferdinand the Bull so appealing is that he lives in his own universe and has his own rules. He’s this large, strapping bull that would look very good in the arena, but that’s not what he’s interested in. He figures out a way to continue to live in his world despite what everybody else thinks. Following your heart is what you should be doing.

Rio Cortez: I don’t remember seeing myself reflected as a Black child in literature when I was young. I found my books through TV and film. When I was 8 or 9, John Singleton released Poetic Justice, and what I took from that was that I wanted to read more Maya Angelou poems. That led me to other poets, like Langston Hughes. In Sister Act 2, there’s a scene where Whoopi Goldberg advises Lauryn Hill to read Letters to a Young Poet. I remember I won a poetry prize when I was in second grade. The prize was Where the Sidewalk Ends by Shel Silverstein, and I asked to swap it at my local Barnes & Noble for Rilke’s Letters to a Young Poet—which was completely beyond what I was able to think about then, but it made me think about poetry.

Lichtenfeld: Jennifer Mack-Watkins’s work celebrates, in her words, “the beauty, importance, and complexity of positive representation of African American children.” What are your thoughts on the state of Black representation in children’s literature today and, perhaps, how it has changed over time? Is positive representation of African Americans something that figures prominently in your own work?

Steptoe: I think about sneakers. When I was young, all the sneakers looked the same. The only difference was the color and the logo. Now, sneakers come in all shapes, sizes, colors, styles. Growing up, seeing books that represented Black people, we were [portrayed as] victims of racism. There was no room for us to maneuver and be full people. Now, I see a lot of people being allowed to tell lots of different stories. It’s not like the stories weren’t there, but we weren’t allowed to speak these stories. Speaking these stories gives people like us power. That’s still something that we’re fighting for today.

In terms of mainstream publishing, we have to look not just at Black and Brown people writing and illustrating books—we also have to talk about who’s behind the scenes in publishing, and who’s behind the scenes in education, because a great number of books being sold are going to educational institutions and school libraries.

We have to think in general about the education of America, and how states are allowed to create their own version of history—their own version of slavery, of Jim Crow. That leads to people doing crazy things like storming the Capitol building. Right now, children’s books about people of color make up about four or five percent of the books that are published each year, but we’re 50 percent of the population. There’s a lot more growing for us to be doing.

Cortez: I’ve worked in publishing for 10 years off and on, and it has felt more acutely different to me in the last 12 months than over the arc of my career. My concern is sustainability. I keep listening for words like “saturation,” these trigger words that say to me, “Okay, we gave it a shot, and we’re going to go back to what we’re used to doing.” But I’ve seen Black artists and writers able to advocate for themselves in new ways. Say, for example, that I want to work with a Black illustrator. Those conversations are changing. They’re still not close to where they need to be, but I have felt a little bit of a change. I’m able to say that it’s important to me to work with a Black editor, or with an imprint that works with diverse voices.

Minter: I can see a lot of changes in the industry, but it still feels limiting to me as far as the types of books that I’m asked to do. I enjoy illustrating all manner of things, and the characters in my books are generally going to be Black characters, because that’s my perspective. But I would like to have a much wider range of stories. I really like nature, insects, machines, science fiction, fantasy, surrealism, nonsense. I like to put these things in my artwork, but publishers don’t seem interested in that type of work coming from me. Things are still in their infancy in terms of recognizing the nuance to the stories that we have to tell.

There’s an organization called Diverse Book Finder that looks at the books being published in a deep and systematic way to understand why we are not seeing more books that represent more aspects of the people in the world community.

Steptoe: I also want to bring up the marketing budget. There are situations where you have non-people-of-color creating stories about people of color that are being pushed, and those books are making millions of dollars. When you have people of color making books about people of color, they're not getting publicity.

Cortez: I can think of several books like that. Publishers think, “This is for this group of people,” as opposed to, “This is a story that everybody ought to be reading.” Before a book even enters the world, there are factors that are predetermining the wideness of its readership, and there are not enough resources going into the already limited number of books by Black creators.

During the Q&A period, an audience member asked about introducing her granddaughter to Little Black Sambo, a book she remembered fondly from her own childhood. She also asked for suggestions of other books about people of color that she could share with her granddaughter.

Minter: I remember that book, too. I think it’s good to be aware of its existence, but as far as it having anything to teach you about Black culture, I don’t think that there’s anything there, or that there ever was anything there. It’s like the gruel that they feed you in prison, or in a dungeon. It’s bread and water.

Steptoe: I’ll put it to you this way. It might be considered offensive for you to pull out Little Black Sambo when we have so many books that are beautiful, that are written by Black people, that talk about Black experiences from a Black person’s viewpoint, that have so much more love. Think about love when you’re thinking about these books. It’s not just going to help Black people for your children to have these books. If you give your child the wrong book, they’re going to be confused. Then they’re going to go out into the world and say, “This is not the way this was portrayed to me in this book.” A lot of times, confusion brings anger. It’s better to give your grandchild something that was made in love, so that when they go out into the universe, they bring that love with them.

Watch the full video here, or jump directly to the following segments, which are not excerpted above:

Thoughts here from each participant about how children’s literature fits into their artistic practice as a whole

A discussion here about the complexity of engaging with Black history in children’s books

The full discussion about Little Black Sambo and about finding and supporting books by diverse voices here

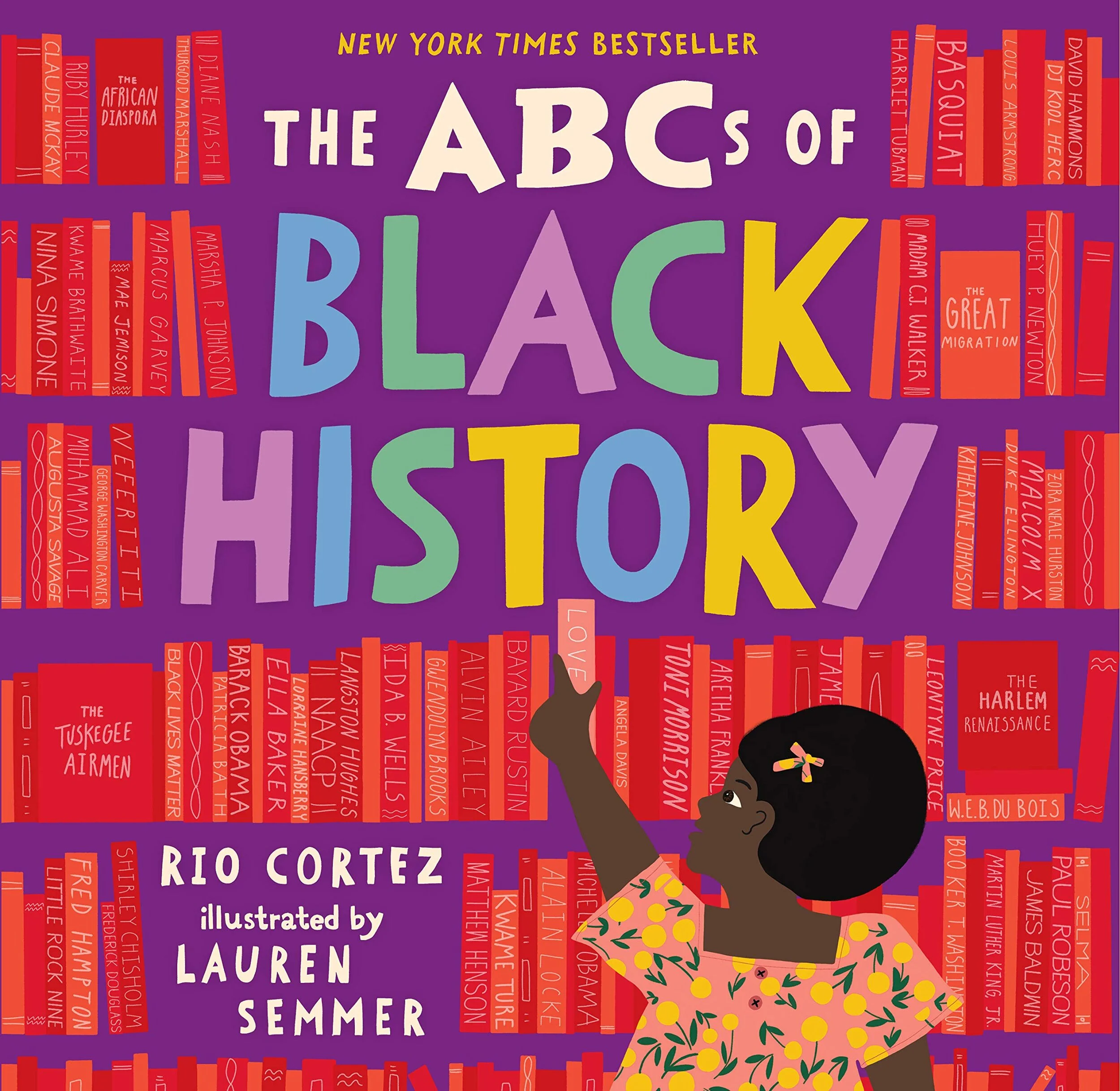

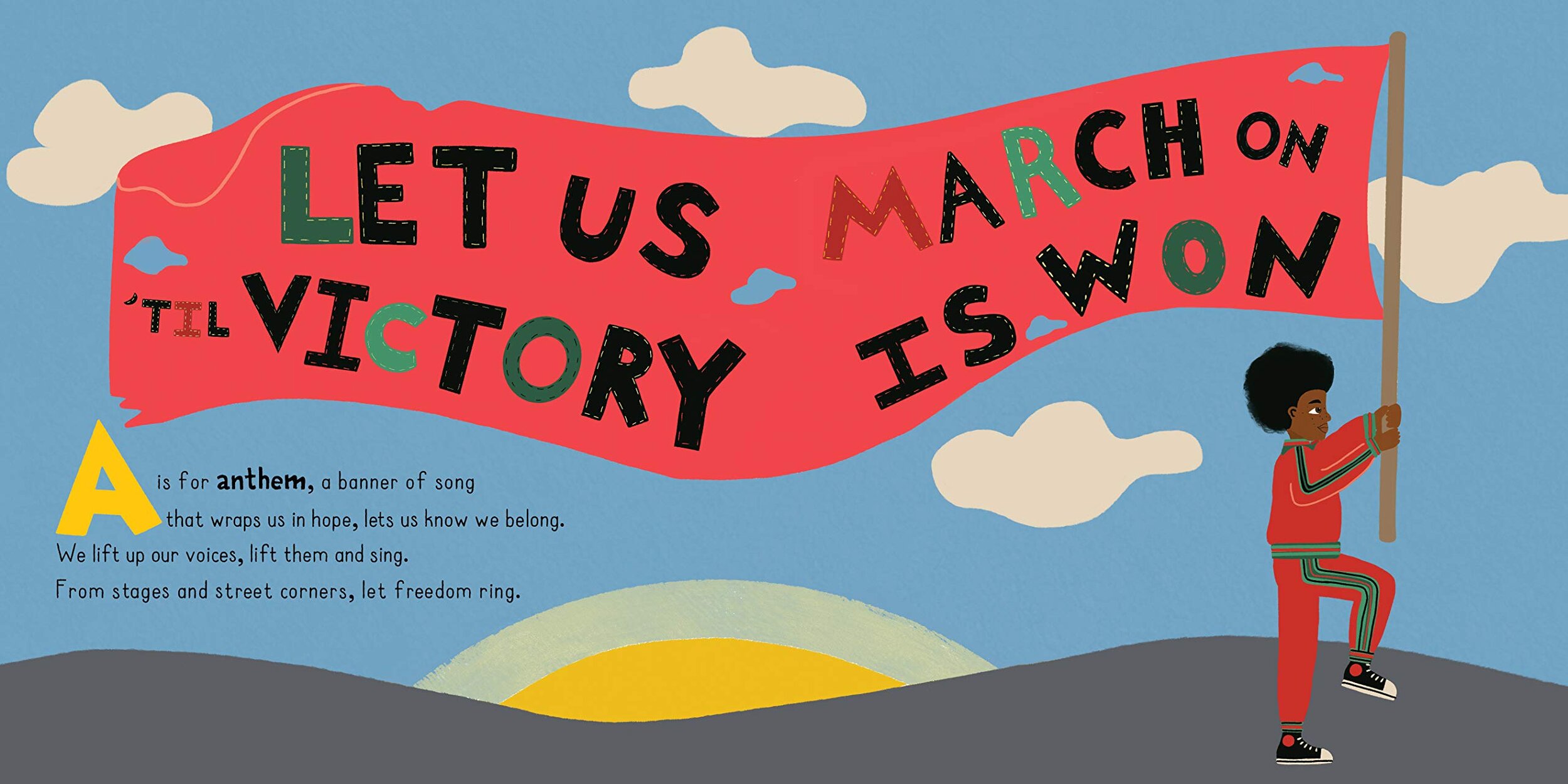

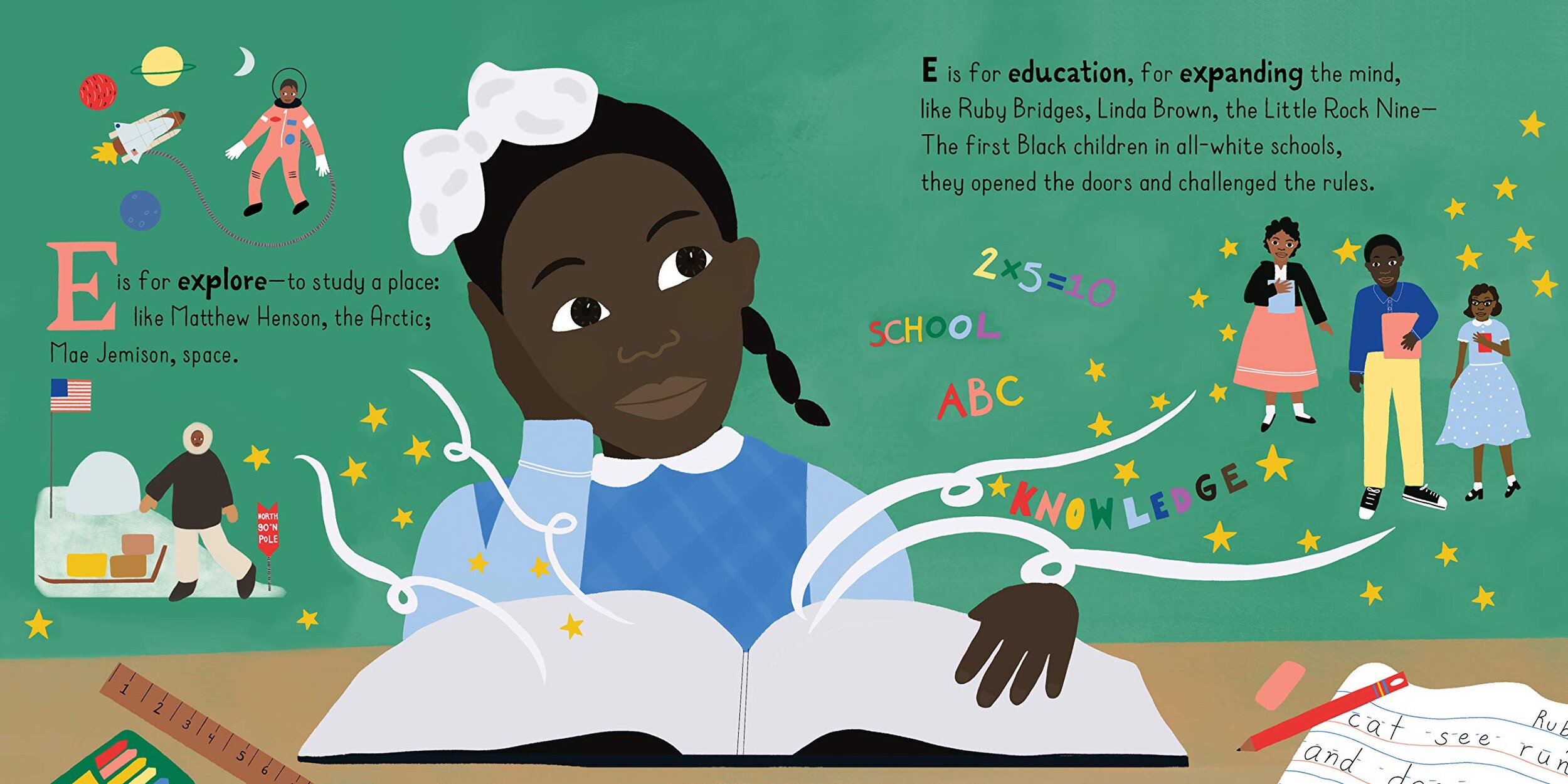

Rio Cortez is the New York Times bestselling author of The ABCs of Black History and I Have Learned to Define a Field as a Space Between Mountains. She is a Pushcart-nominated poet who has received fellowships from Poet’s House, Cave Canem, and Canto Mundo Foundations. Born and raised in Salt Lake City, she now lives, writes, and works in Harlem.

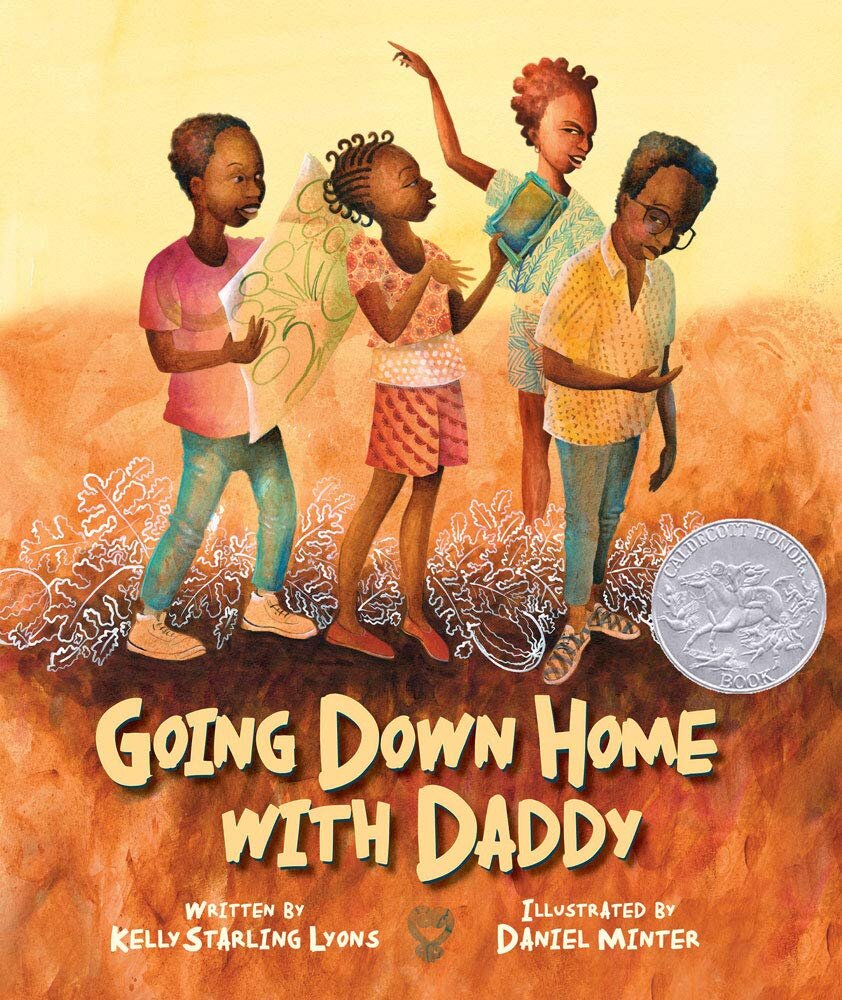

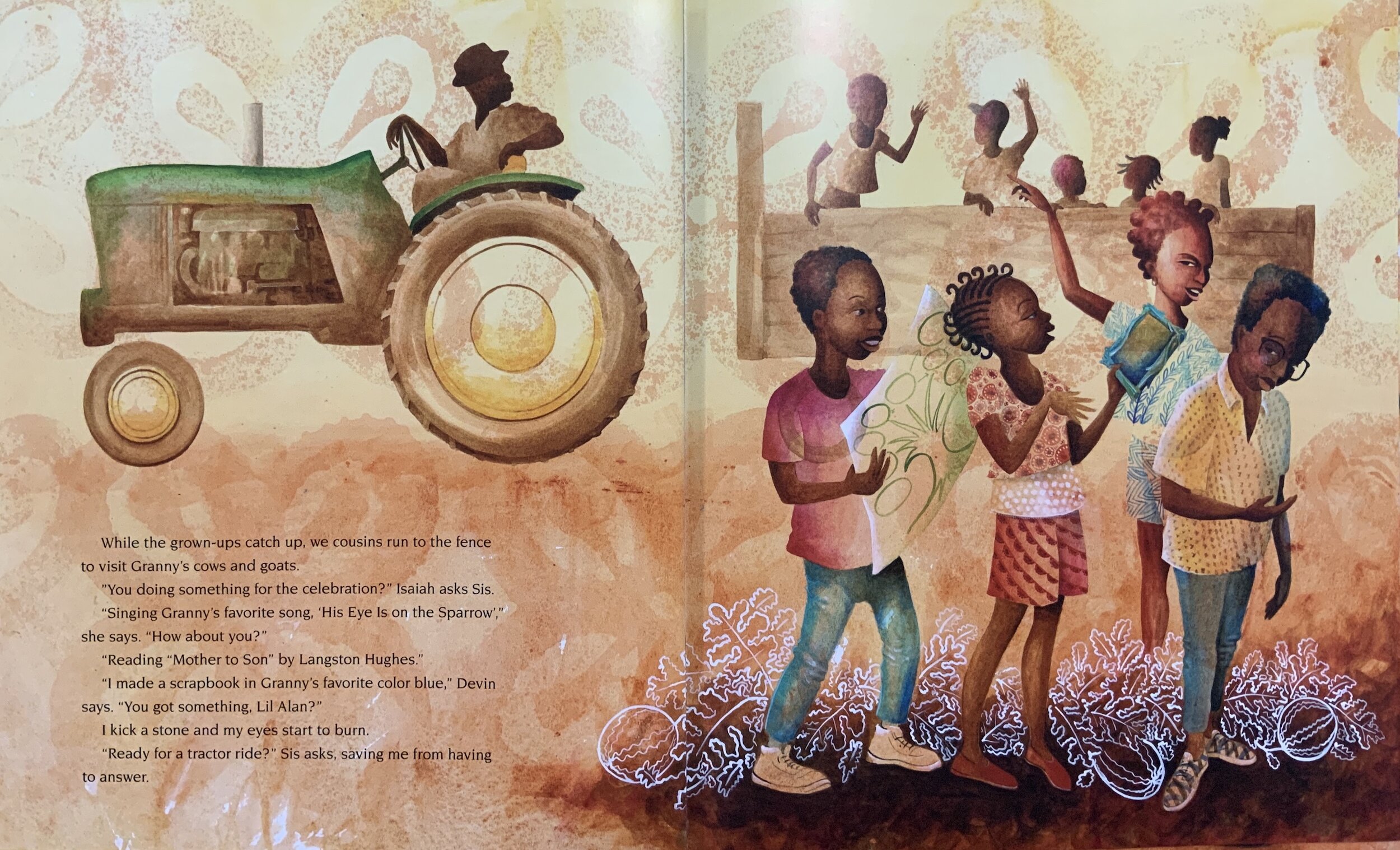

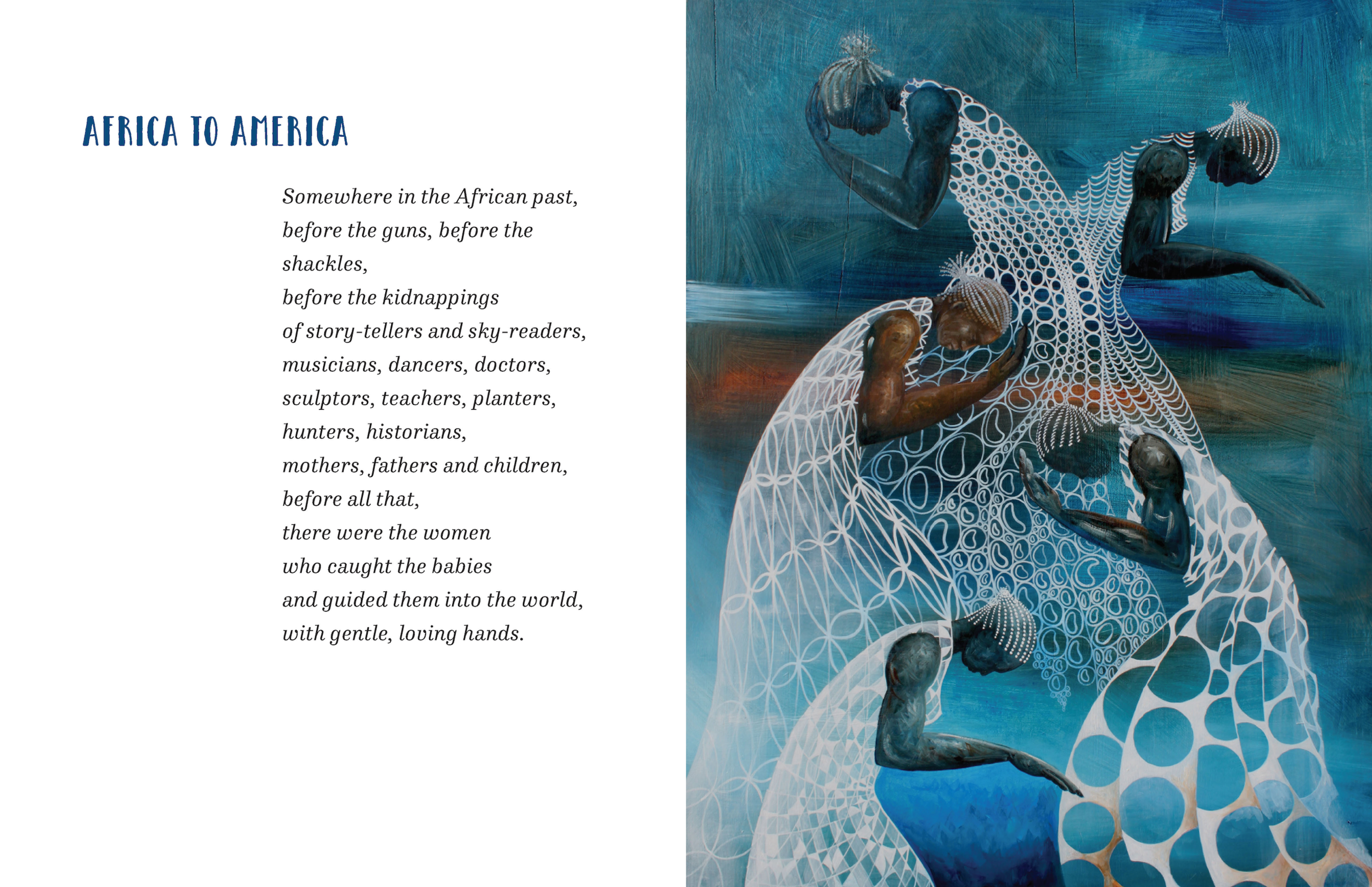

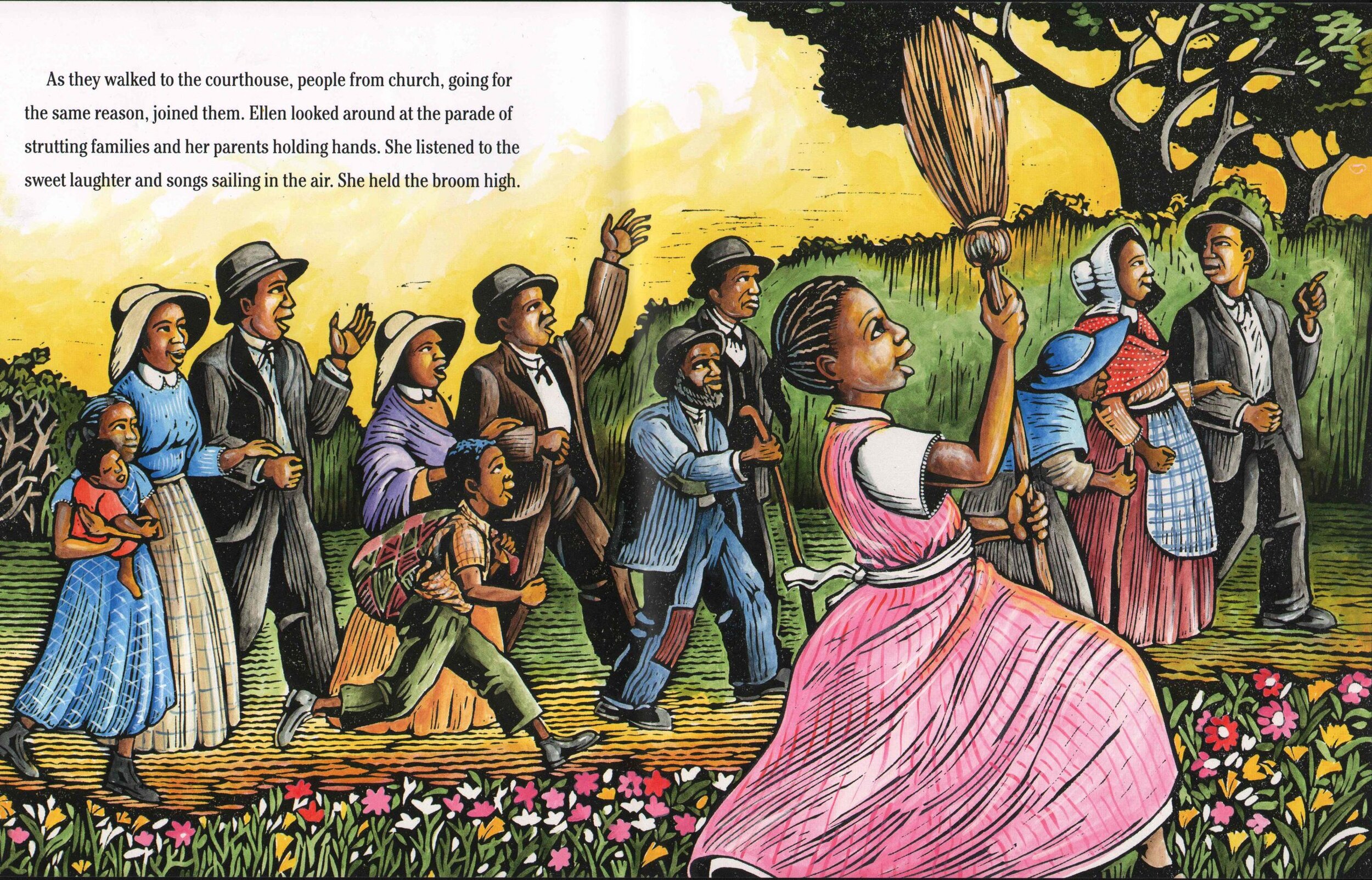

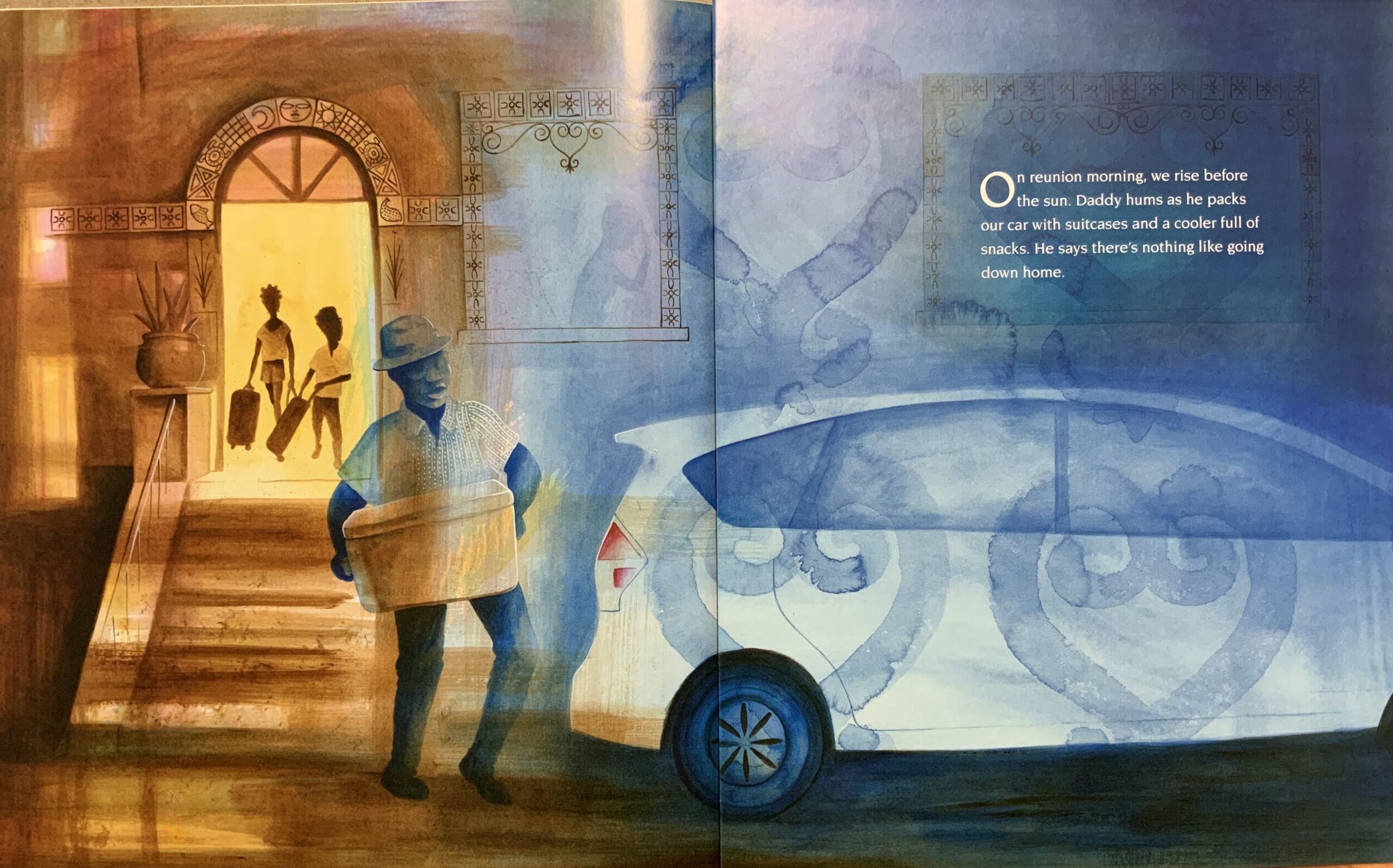

Daniel Minter has illustrated over a dozen children’s books, including Going Down Home with Daddy, which won a 2020 Caldecott Honor, and Ellen’s Broom, which won a Coretta Scott King Illustration Honor. He was also commissioned in both 2004 and 2011 to create Kwanzaa stamps for the U.S. Postal Service.

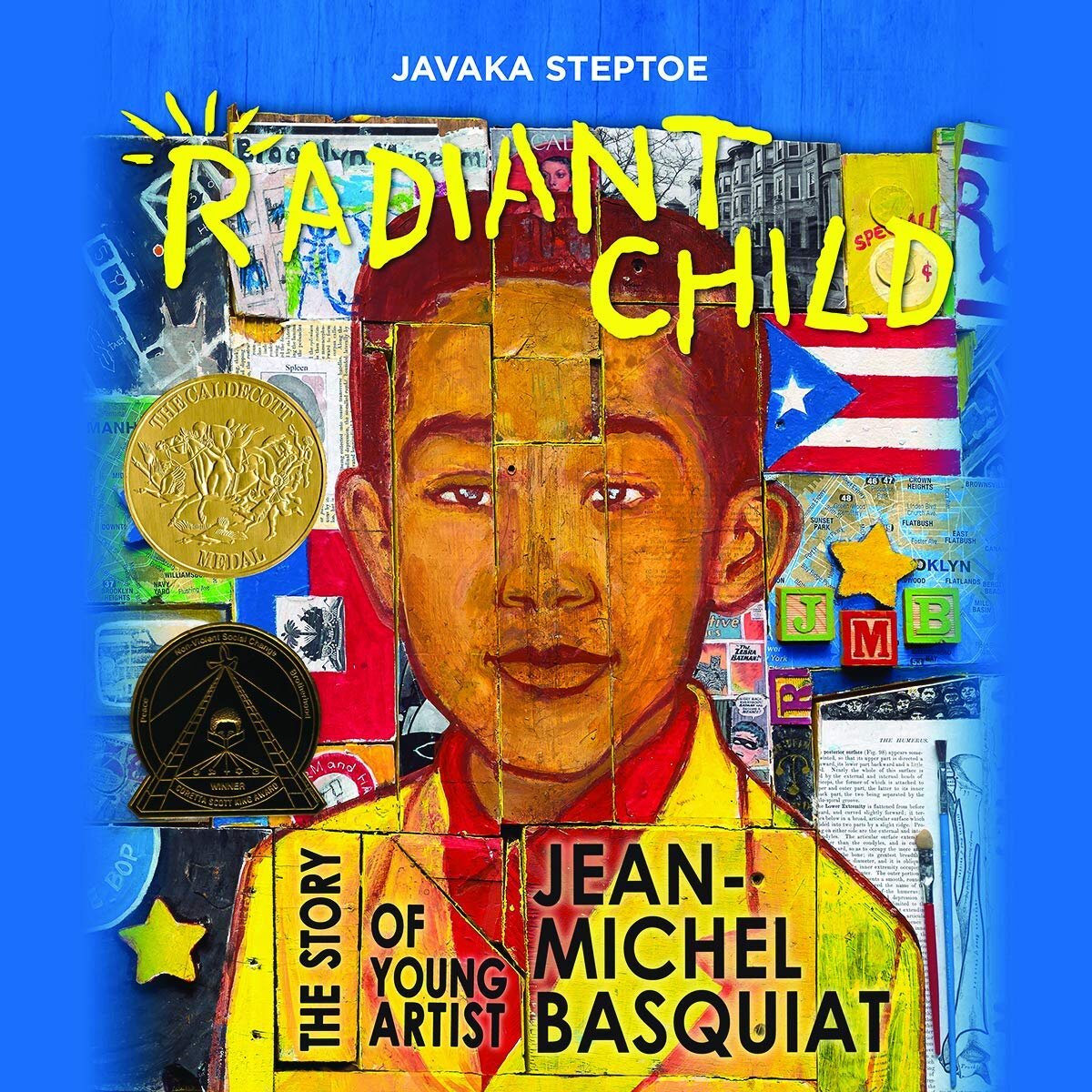

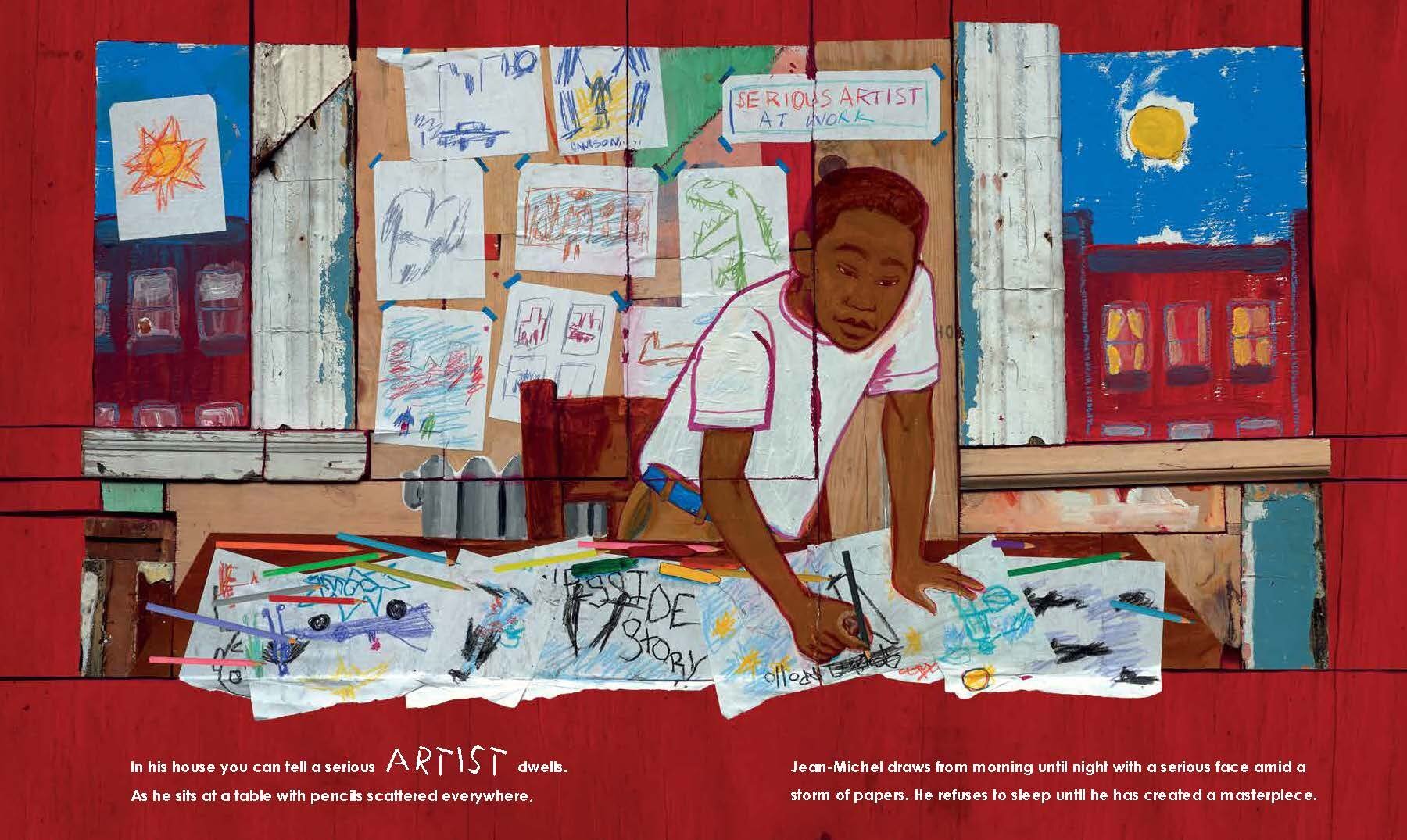

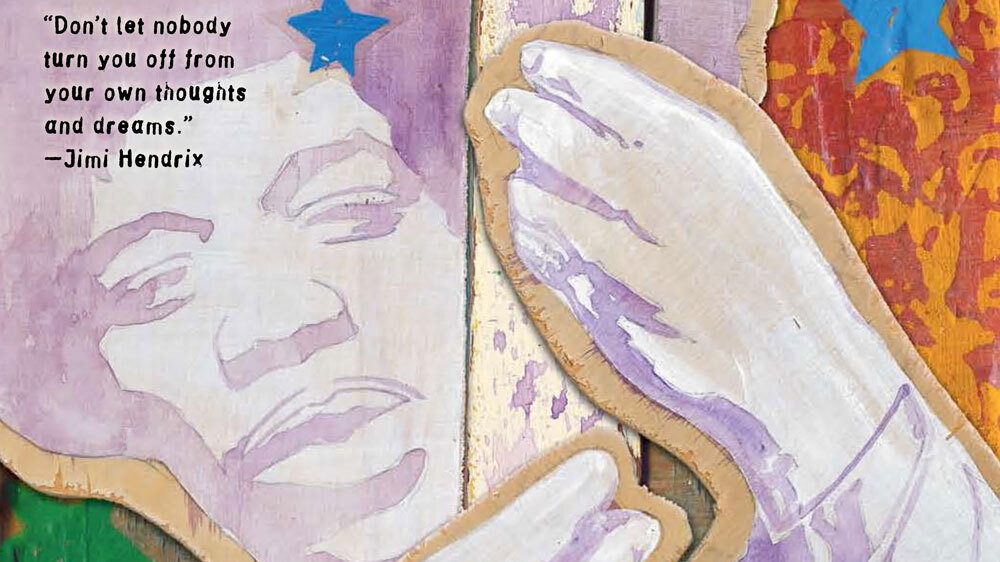

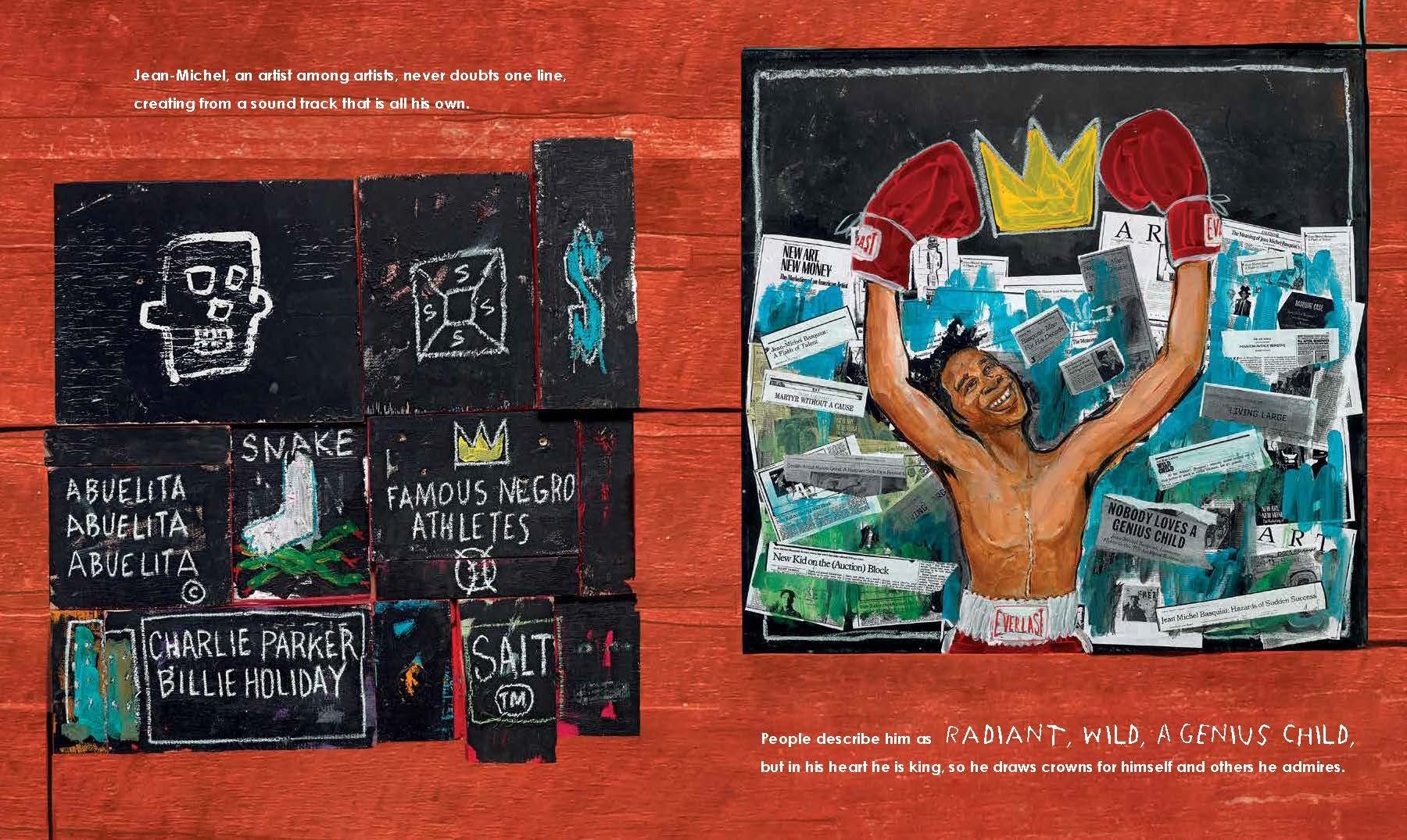

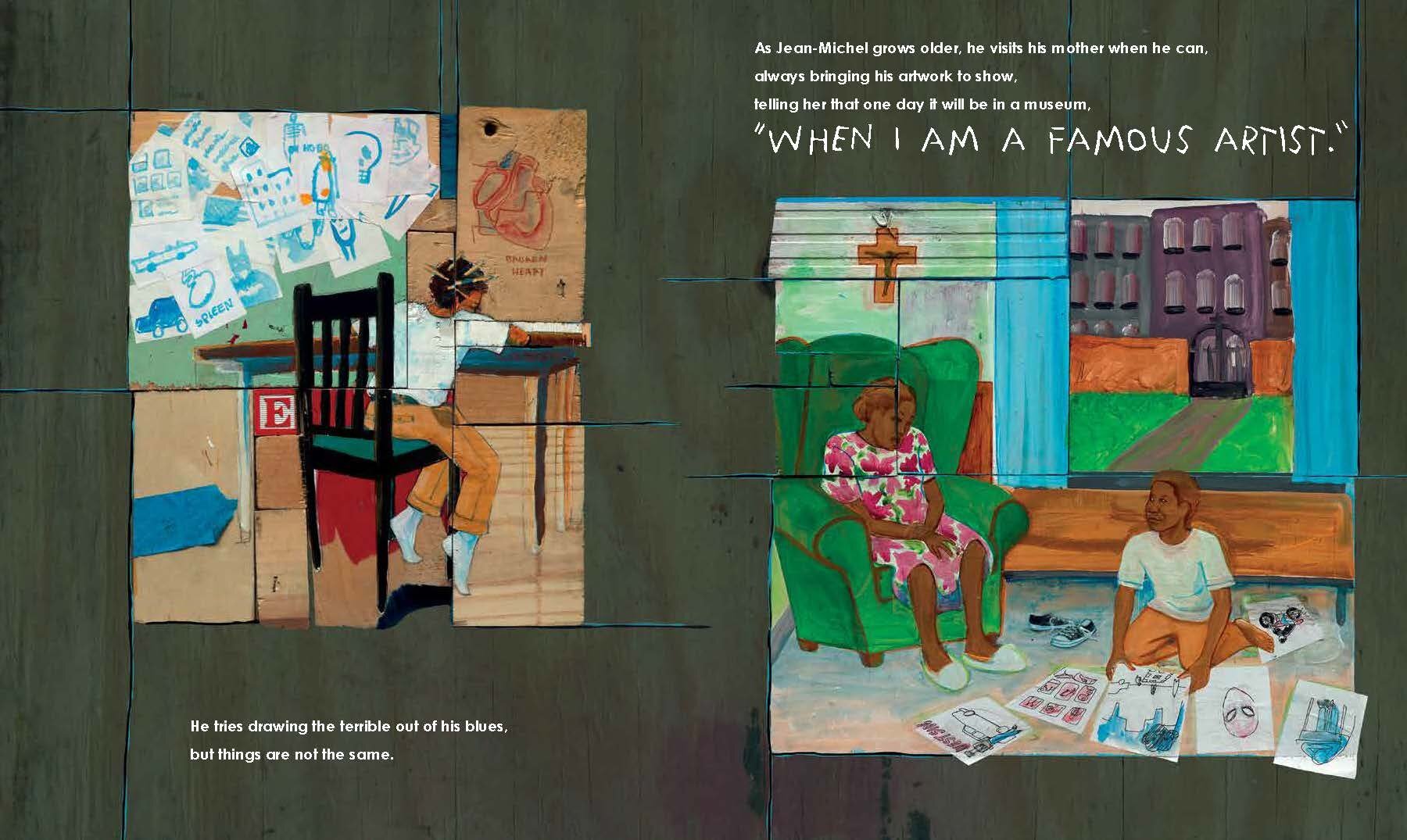

Javaka Steptoe is a Caldecott and Coretta Scott King Illustrator award-winning artist, designer, and illustrator. His debut picture book, In Daddy’s Arms I Am Tall, won the Coretta Scott King Award, and Jimi: Sounds Like a Rainbow (written by Gary Golio) received a Coretta Scott King Honor. He is the author and illustrator of the Caldecott Award-winning Radiant Child: The Story of Young Artist Jean-Michel Basquiat.

Books by Cortez, Minter, and Steptoe are available for purchase in the BMAC Gift shop.